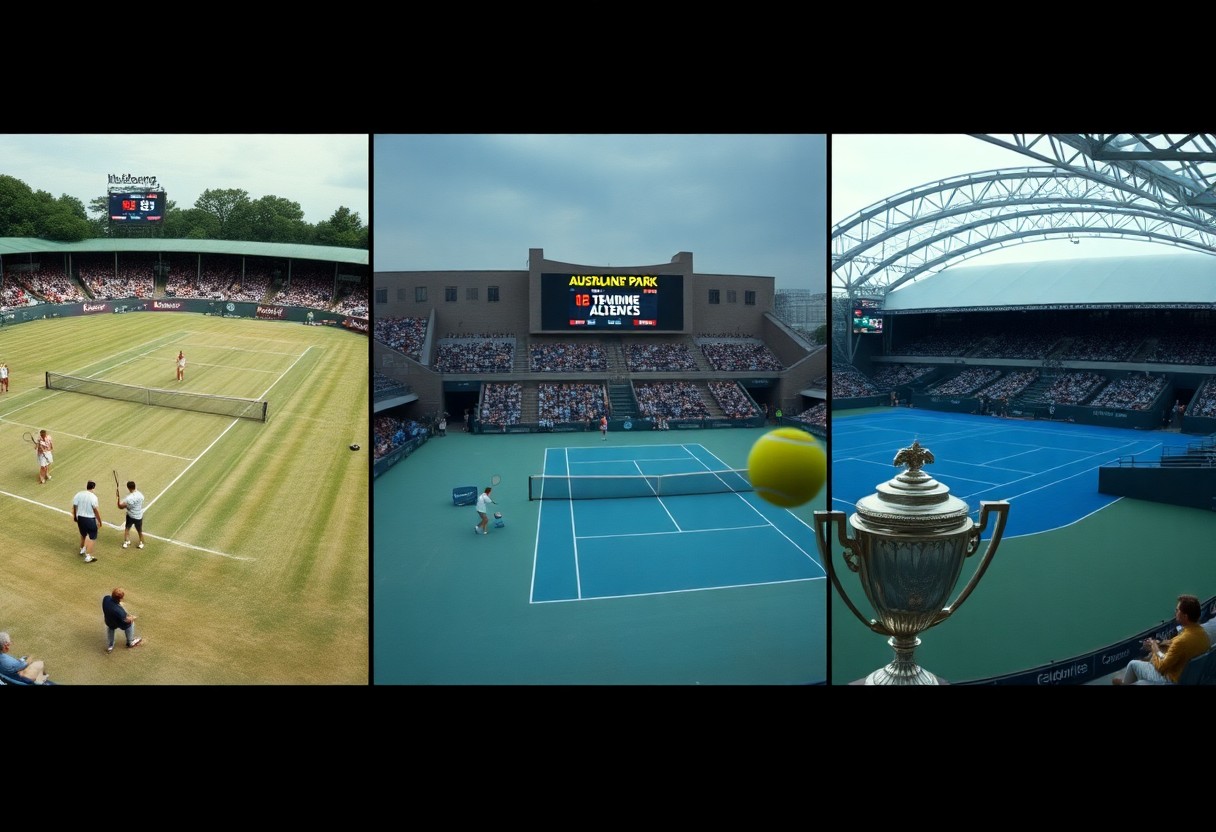

Over the past century the Australian Open transformed from a regional grass-court tournament into a modern Grand Slam, driven by the 1988 switch to hard courts, calendar changes and stadium upgrades. The event’s rise brought global prestige and technological innovation in player preparation, while also presenting dangerous extreme-heat conditions that shaped scheduling and rules. This guide traces that evolution, its impact on playing style, and the tournament’s ongoing quest for competitive and infrastructural excellence.

The Types of Courts Used in the Australian Open

- Grass Courts

- Hard Courts

- Clay Courts

- Rebound Ace

- GreenSet

| Grass Courts | Used until 1987; very fast with a low, often unpredictable bounce, favoring serve-and-volley specialists. |

| Rebound Ace | 1988-2007; cushioned hard court with tackiness in high heat that created slip and injury concerns. |

| Plexicushion | 2008-2019; acrylic multilayer system designed to standardize pace and reduce joint impact for players. |

| GreenSet | 2020-present; acrylic hardcourt with consistent speed and rebound used on all main showcourts at Melbourne Park. |

| Clay Courts | Not used for the main draw at the Australian Open; present only in some practice/lead-up events and training facilities. |

Grass Courts

The pre-1988 grass era produced low, skidding bounces that rewarded quick serves and net play; maintenance demanded daily mowing and watering, and champions like Rod Laver exploited the surface’s blistering pace, with matches often finishing in fewer sets than on modern hard courts.

Hard Courts

The move to hard courts began in 1988 with Rebound Ace and evolved through Plexicushion to GreenSet, shifting play toward baseline rallies; Novak Djokovic’s ten Australian Open titles since 2008 underline how the surface favors endurance, precision and consistent footwork.

Rebound Ace (1988-2007) contained a rubberised cushion that absorbed shock but became sticky under intense heat, contributing to sliding incidents and complaints from players; Plexicushion (2008-2019) aimed to slow the game slightly and reduce injuries with layered acrylic, while GreenSet (from 2020) standardized bounce and court speed across Rod Laver Arena and other showcourts, helping referees and players adapt strategies more predictably.

Clay Courts

Clay is slow with a high, looping bounce that rewards topspin and endurance; although the Australian Open has never staged its main draw on clay, many players use clay-court training to sharpen movement and point construction ahead of the season.

Surface specialists on clay-seen most prominently at Roland Garros-demonstrate how sliding technique and heavy topspin alter match construction; Australian Open scheduling and Melbourne’s hard, often hot conditions make clay impractical for the tournament itself, so clay appears mainly in warm-up events and private practice courts where players fine-tune baseline stamina and spin-heavy tactics. Thou can see how each surface change reshaped tactics and champions.

Key Factors in the Evolution of the Australian Open

Shifts in surface technology, scheduling and climate management reshaped play from 1905 to today, altering bounce, injury risk and match length. Innovations like Rebound Ace (1988-2007), Plexicushion (2008-2019) and GreenSet (2020-present) each changed ball speed and player tactics, while stadium retractable roofs and electronic officiating improved reliability. Thou emphasize the tournament’s move to Melbourne Park (1988), the Open Era (1969) inclusion of professionals, and the adoption of an Extreme Heat Policy.

- Australian Open

- Rebound Ace

- Plexicushion

- GreenSet

- Open Era

- Melbourne Park

- Extreme Heat Policy

Historical Context

Established in 1905 as the Australasian Championships, the event rotated cities and struggled to attract Europe-based pros until air travel and prize money increased; the 1969 Open Era allowed professionals, boosting fields, and relocating permanently to Melbourne Park in 1988 centralized facilities and media exposure, transforming it into a true Grand Slam.

Technological Advances

Surface chemistry and stadium engineering altered match dynamics: Rebound Ace produced higher bounce and heat retention, leading to a switch to Plexicushion in 2008 and then GreenSet in 2020 for more consistent pace; meanwhile, retractable roofs and electronic review systems reduced weather disruption and officiating errors.

Surface changes directly impacted player performance and injury patterns-Rebound Ace’s tackiness correlated with complaints about ankle strain, prompting the 2008 move to Plexicushion for firmer, cooler play; subsequent adoption of GreenSet sought to standardize bounce and speed for both men’s and women’s matches, while Hawk-Eye and stadium roofs improved scheduling, broadcasting and match fairness.

Player Adaptation

As courts slowed and rallies lengthened, players shifted from classic serve-and-volley styles to powerful, consistent baseline games; modern champions adapted with enhanced endurance, tactical variety and slide control, and competitors now prepare for Melbourne’s extreme summers through targeted heat adaptation and recovery protocols.

Coaching and sports science accelerated that shift: teams employ bespoke data analysis, VO2 testing, heat-acclimation sessions and on-court cooling tactics (ice towels, misting, electrolyte strategies), while tactical training emphasizes positional depth and constructing points on slower hard courts to exploit opponents’ movement limitations.

Step-by-Step Journey from Local Tournament to Grand Slam

Step-by-Step Journey Summary

| Stage | Highlights |

|---|---|

| Early local era | Founded in 1905 as the Australasian Championships; small domestic fields and limited international travel. |

| National consolidation | Rotated among cities to build audiences and infrastructure across Australian states. |

| Open Era | 1969 allowed professionals, elevating standard and international entries. |

| Calendar & venue reform | 1977 had two editions during a calendar shift; moved to Melbourne Park in 1988. |

| Modern Grand Slam | Stadium upgrades, broadcast deals and multi-million-dollar purses (equalized by 2001) sealed global status. |

Early Beginnings

By 1905 the Australasian Championships began with mainly domestic entrants and modest draws; organizers rotated venues to grow reach while local champions like Rodney Heath and repeat state rivalries generated newspaper coverage that slowly expanded the tournament beyond club-level audiences.

Major Milestones

Milestones that shifted perception include the start of the 1969 Open Era, the dual events in 1977 during calendar realignment, and the relocation to Melbourne Park in 1988, each raising field quality, spectator interest and international media attention; later reforms such as equal prize money by 2001 modernized the event further.

For instance, the 1969 Open Era coincided with Rod Laver completing his second calendar Grand Slam, boosting prestige; the 1977 anomaly forced a stable January schedule and the 1988 move brought Rod Laver Arena (capacity ≈14,820), new court surfaces and broadcast contracts that expanded global viewership.

Transition to Grand Slam Status

Improvements in air travel and player logistics, combined with the 1969 professional era and the venue/scheduling reforms of 1988, shifted the event from a regional championship to a calendar highlight that attracted top international talent and larger commercial partners.

Broadcast expansion and stadium innovations, including retractable roofs and enhanced spectator facilities, convinced multi-time champions and top-ranked players to prioritise the tournament, supported by multi-million-dollar prize pools and global media deals that ultimately cemented Grand Slam status.

Pros and Cons of Different Court Surfaces

Pros vs Cons of Surfaces

| Play Speed | Grass: fastest, Hard: medium-fast, Clay: slow – affects serve dominance vs baseline rallies |

| Bounce Consistency | Hard: most consistent; Grass: low and variable; Clay: high and predictable |

| Rally Length | Clay: longer rallies (physical demand); Grass: shortest rallies; Hard: intermediate |

| Injury Risk | Hard: higher joint impact; Grass: slip risk; Clay: less abrupt joint stress |

| Maintenance | Grass: costly and weather-sensitive; Clay: regular rolling/watering; Hard: lowest upkeep |

| Player Style Rewarded | Serve-and-volley on grass, power/flat hitters on hard, grinders/slide experts on clay |

| Weather Sensitivity | Grass and clay more affected by rain; hard courts drain and resume play faster |

| Historical Impact | Grass shaped early AO champions; hard courts expanded global competitive depth |

Advantages of Grass

Grass accelerates play with a low, skidding bounce, rewarding big servers and slice; serve-and-volley specialists historically dominated (Pete Sampras and Roger Federer combined for 14 Wimbledon titles), and matches often finish quicker – average rallies tend to be under five shots – making grass ideal for players seeking short, high-impact points and tactical net play.

Disadvantages of Hard Courts

Hard courts produce a consistent, medium-fast surface but impose greater cumulative load on knees and ankles, increasing wear for players who play 60-80 matches a year on tour; surfaces like Plexicushion and GreenSet altered shock absorption over time, affecting career longevity for some athletes.

Beyond general wear, variability between hard-court formulations matters: the Australian Open used Rebound Ace until 2007, switched to Plexicushion (2008-2019) and adopted GreenSet in 2020, each change shifting ball speed and slide. That evolution influenced player performance patterns – for example, baseline grinders noticed fewer micro-slides on newer mixes, while power servers benefited from firmer responses; overall, repetitive impact and limited shock absorption remain the main long-term concerns.

Comparing Clay Court Dynamics

Clay slows the ball and produces a high, gripping bounce, extending rallies and favoring topspin-heavy baseliners; Rafael Nadal’s dominance at Roland Garros (14 titles) exemplifies how sliding technique, endurance, and point construction matter far more on clay than on grass or typical hard courts.

Clay Dynamics: Key Effects

| Ball Behavior | Slower speed, higher kick – benefits heavy topspin and deep returns |

| Movement | Sliding allows energy dissipation but requires specific footwork and balance |

| Rally Profile | Longer points increase aerobic demand and tactical variation |

| Match Duration | Higher likelihood of matches exceeding three hours; notable long matches at French Open |

| Surface Maintenance | Regular watering/rolling; weather delays more common than on hard courts |

Drilling deeper, clay’s combination of slower pace and sliding mechanics shapes training and injury profiles: players often develop stronger hip stabilization and endurance but face increased risk of overuse injuries from extended baseline exchanges; coaches tailor conditioning – for instance, Nadal’s clay-specific regimen emphasizes lateral stability and recovery to handle multi-hour five-set battles at Roland Garros.

Tips for Players Competing in the Australian Open

Adapting quickly to the Australian Open environment means prioritizing heat adaptation, surface-specific practice and match-simulated fitness; many players arrive 10-21 days early to acclimatize to heat that often exceeds 35°C and to train on the tournament’s GreenSet surface. Use recovery tools like ice baths and compression to lower injury risk, and build match endurance-recall Djokovic’s 5h53m 2012 semi-final as a benchmark for extreme stamina. Hydration and short-point construction preserve energy. This

- Acclimatization: arrive 10-21 days early

- Surface practice: train on GreenSet or similar

- Heat management: plan hydration and cooling strategies

- Recovery: ice baths, compression, sleep scheduling

- Mental routines: visualization and pressure simulations

Preparation Strategies

Schedule 2-3 high-intensity sessions weekly and replicate AO conditions by hitting on GreenSet courts and training in 30-35°C settings where possible; arrive with a taper plan, log sleep and nutrition, and include 30-45 minute on-court match simulations plus specific legs-and-core sessions to handle five-set demands and fast baseline exchanges.

Mental Conditioning

Implement daily 10-15 minute visualization and breathing routines, rehearse cue words for momentum shifts, and run pressure drills-play simulated tiebreaks with crowd noise and defined penalties to build tolerance for AO’s noisy, high-stakes atmosphere.

Sports psychologists advise combining exposure therapy with micro-routines: for example, practice 20-30 simulated tiebreaks per week, use a 4-4-4 breathing pattern between games, and deploy single-word cues like “reset” to shorten cognitive recovery between points; Novak Djokovic’s in-match refocusing and Rafa Nadal’s pre-serve rituals illustrate how consistent, repeatable habits increase clutch performance under heat and crowd pressure while lowering injury risk from mental fatigue.

On-Court Techniques

Prioritize a condensed point strategy in extreme heat, attack the second serve with aggressive returns, use low slices to disrupt rhythm, and emphasize first-serve percentage-practicing serve patterns that win 65%+ of first-serve points reduces time on court and exposure to scorching midday conditions.

This detailed on-court plan centers on targeting opponents’ weaker wings (often the backhand), mixing flat and kick serves to the body, opening the court with angled inside-out forehands, practicing transitional volley patterns for quicker point closure, and tracking point-length stats in practice so you can enforce 3-6 shot point templates that minimize endurance drain while maximizing return-on-effort under the unique hard courts and extreme-heat demands of the Australian Open.

The Impact of the Australian Open on Global Tennis

Shifting the calendar and expectations, the Australian Open now drives season momentum with over 800,000 spectators and a global TV reach to more than 200 territories; its AUD 76.5 million prize pool in 2023 raises standards for other events, while champions like Novak Djokovic (10 AO titles) have boosted the Slam’s international prestige. Tournament innovations – from the Extreme Heat Policy to expanded night sessions – have set behavioral and safety benchmarks across the tour.

Cultural Significance

Anchoring Melbourne’s summer identity, the Open blends sport and festival culture: Rod Laver Arena sits alongside fan zones, live music and international cuisine, attracting diverse global crowds and celebrity attendance. Grassroots impact shows in rising academy enrollments across the Asia‑Pacific, and the tournament’s high‑profile ceremonies and Indigenous acknowledgements amplify tennis as a cultural export for Australia.

Economic Contributions

The event injects well over AUD 300 million annually into Victoria, supports thousands of jobs across hospitality and transport, and funnels income into clubs and academies; combined with the AUD 76.5 million prize pool and sponsorship/broadcast revenues, the Open creates a significant financial ripple through the local and international tennis economy.

Ticket sales, corporate hospitality and broadcast rights form the backbone of that economic impact: two‑week attendance and international visitors drive hotel occupancy often above 90% in central Melbourne, while sponsorship and media deals fund stadium upgrades and community programs. The precinct’s multi‑year redevelopments and year‑round events increase long‑term tourism value, and temporary staffing plus volunteer programs deliver both direct wages and skills‑based benefits to the local workforce.

Influence on Future Tournaments

By pioneering player‑welfare measures and infrastructure – including three retractable roofs, extensive night sessions and a formal Extreme Heat Policy – the Australian Open has pushed rivals to modernize facilities, adjust scheduling, and elevate prize money, setting practical templates other tournaments now emulate when balancing entertainment and athlete safety.

More broadly, the Open’s approach to integrating fan experiences, broadcast technology and player services has changed tournament design: examples include Wimbledon’s roof additions (Centre Court 2009, No.1 2019) and expanded night sessions at multiple ATP/WTA events, while emerging tournaments in Asia and the Middle East increasingly mirror the Open’s investment profile to attract top players and global media partners.

Conclusion

Hence the Australian Open has transformed from a modest grass-court national event into a globally celebrated Grand Slam, driven by surface changes, venue modernization, professionalization, and technological innovation; its embrace of hard courts, improved facilities, and international scheduling solidified its status and ensured continued growth, cultural impact, and competitive prestige in the tennis calendar.

FAQ

Q: Why did the Australian Open switch from grass courts to hard courts?

A: The change coincided with the move from Kooyong to Melbourne Park in 1988. Grass demanded intensive maintenance, produced uneven bounces as play wore the surface down, and limited scheduling in hot or wet conditions. Moving to an acrylic-cushioned hard court (initially Rebound Ace, later Plexicushion, now GreenSet) provided a more consistent, lower-maintenance playing surface, enabled installation of retractable roofs and night sessions, and made scheduling and broadcast reliability far better for a global Grand Slam.

Q: How did surface changes affect playing styles and the list of champions?

A: Grass courts favored serve-and-volley players and quick points, so early champions often relied on big serves and net skills. Hard courts slowed the ball slightly and produced a more predictable bounce, encouraging baseline rallies, longer points, and greater emphasis on endurance and groundstroke depth. As a result, the tournament’s champion profile shifted toward all-court and baseline-dominant players in the hard-court era, while modern training, racket and string technology further amplified power and consistency across surfaces.

Q: When and why did the Australian Open become one of the truly major Grand Slams?

A: The tournament’s status rose steadily, but the move to Melbourne Park in 1988 and subsequent investments in facilities, prize money and global broadcasting were turning points. Earlier in the 20th century travel distance and calendar instability limited top-player attendance; improved scheduling (fixed January slot), the addition of covered stadiums, expanded night sessions and higher prize funds attracted the world’s best on a consistent basis. Those changes transformed the event into the fully modern Grand Slam it is today.